-

This article brings to the fore important points such as the desperate need for more efficient water practices and the inappropriately low cost of water (for the most part in CA we pay for conveyence and cleaning). Read on!

Will The Next War Be Fought Over Water?

Just as wars over oil played a major role in 20th-century history, a new book makes a convincing case that many 21st century conflicts will be fought over water.

In Water: The Epic Struggle for Wealth, Power and Civilization, journalist Steven Solomon argues that water is surpassing oil as the world’s scarcest critical resource.

Only 2.5 percent of the planet’s water supply is fresh, Solomon writes, much of which is locked away in glaciers. World water use in the past century grew twice as fast as world population.

“We’ve now reached the limit where that trajectory can no longer continue,” Solomon tells NPR’s Mary Louise Kelly. “Suddenly we’re going to have to find a way to use the existing water resources in a far, far more productive manner than we ever did before, because there’s simply not enough.”

One issue, Solomon says, is that water’s cost doesn’t reflect its true economic value. While a society’s transition from oil may be painful, water is irreplaceable. Yet water costs far less per gallon — and even less than that for some.

“In some cases, where there are large political subsidies, largely in agriculture, it does not [cost very much],” Solomon says. “In many cases, irrigated agriculture is getting its water for free. And we in the cities are paying a lot, and industries are also paying an awful lot. That’s unfair. It’s inefficient to the allocation of water to the most productive economic ends.”

At the same time, Solomon says, there’s an increasing feeling in the world that everyone has a basic right to a minimum 13 gallons of water a day for basic human health. He doesn’t necessarily have an issue with that.

“I think there’s plenty of water in the world, even in the poorest and most water-famished country, for that 13 gallons to be given for free to individuals — and let them pay beyond that,” he says.

Solomon says the world is divided into water haves and have-nots. China, Egypt and Pakistan are just a few countries facing critical water issues in the 21st century.

In his book he writes, “Consider what will happen in water-distressed, nuclear-armed, terrorist-besieged, overpopulated, heavily irrigation dependent and already politically unstable Pakistan when its single water lifeline, the Indus river, loses a third of its flow from the disappearance from its glacial water source.”

Solomon notes some good water news, too. The United States has made significant progress in curbing its water use, thanks to market forces and legislation such as the Clean Water Act.

“Our water use between 1900 and 1975 actually tripled relative to population growth,” he says. “Since 1975 to the present day, it has flat-lined. And we still had a population increase of about 30 percent and our GDP continued to grow. So it’s an amazing increase in water productivity.”

_____________________________________________________________

Prologue Of ‘Water: The Epic Struggle For Wealth, Power, And Civilization’ by Steven SolomIn 1763 a twenty-seven-year-old instrument maker named JamesWatt repaired a model of a Newcomen steam engine owned by the University of Glasgow. Britain was in the grip of a dire fuel famine resulting from the early deforestation of its countryside, and many of the primitive engines invented by Thomas Newcomen a half century earlier were working to pump floodwater from coal mines so that more coal could be excavated as a substitute fuel. While repairing the Newcomen machine, Watt had been startled by its inefficiency. Filled with the spirit of scientific inquiry then going on in the Scottish Enlightenment, he determined to try to improve its capacity to harness steam energy. Within two years he had a much-more-efficient design, and by 1776 was selling the world’s first modern steam engine.

James Watt’s improved steam engine was a turning point in history. It became the seminal invention of the Industrial Revolution. Within a matter of decades, it helped transform Britain into the world’s dominant economy with a steam-and-iron navy that lorded over a colonial empire spanning a quarter of the globe. Britain’s pioneering textile factories multiplied their productivity and output by shifting from waterwheel to steam power and relocating from rural riversides to new industrial towns. Steam-driven bellows heated coke furnaces to produce prodigious amounts of cast iron, the plastic of the early industrial age. Watt steam engines helped overcome Britain’s fuel famine by pumping excess water out of coal shafts—and put the discharge to use by supplementing the water supply of the inland canals that had sprung up to expedite the growing shipments of coal from the collieries to the markets. Watt steam engines abetted the rise of urban metropolises, and improved the health and longevity of their residents, by pumping up freshwater from rivers for drinking, cooking, sanitation, and even firefighting. From Watt’s steam engine, a new industrial society took

hold that launched human civilization on an altogether new trajectory. World and domestic balances of power were recast, and mankind’s material existence, population levels, and expectations increased more in just two centuries than they had in all the thousands of preceding years.

Yet as momentous as it was, Watt’s innovation for exploiting steam power was but one of a long list of water breakthroughs that have been causally entwined with major turning points in history—much like the one unfolding before us today. Water has strongly influenced the rise and decline of great powers, foreign relations among states, the nature of prevailing political economic systems, and the essential conditions governing ordinary people’s daily lives. The Industrial Revolution was akin to the Agricultural Revolution of about 5,000 years ago, when societies in ancient Egypt, Mesopotamia, the Indus Valley, and northern China separately began mastering the hydraulic arts of controlling water from large rivers for mass-scale irrigation, and in so doing unlocked the economic and political means for advanced civilization to begin. Ancient Rome rose as a powerful state when it gained dominance over the Mediterranean Sea, and developed its flourishing urban

civilization at the heart of its empire on the flow of abundant, clean freshwater brought by its stupendous aqueducts. The takeoff event and vital artery of China’s medieval golden age was the completion of its 1,100-mile-long Grand Canal, which created a transport highway uniting the resources of its wet, rice-growing, southerly Yangtze region with its fertile, semiarid Yellow River northlands. Islamic civilization’s brilliance was sustained by the trading wealth that accompanied the opening of its once-impenetrable, waterless deserts by long-distance camel caravans that spanned from the Atlantic to the Indian oceans. Open oceanic sailing was the West’s breakthrough route to world dominance, which it built upon through its leadership in steam, hydraulic turbines,

hydroelectricity, and other water technologies of the industrial age. The sanitary and public health revolutions of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries that underpinned mankind’s unprecedented demographic transformations sprung from efforts to provide freshwater free of filth and conditions inhospitable for disease-carrying organisms. America’s historical rise, too, was explained in important part by its mastery and integration of its three diverse hydrological environments: exploitation of the industrial waterpower and transport potential of the

year-round rivers in its temperate, rainy eastern half, highlighted by the catalytic Erie Canal; the naval domination of its two ocean frontiers, and ascendance to world leadership, following the epic building of the Panama Canal; and the triumph over its arid Far West by its pioneering innovation of giant, multipurpose dams inaugurated with its Depression-era Hoover Dam. The worldwide diffusion of giant dams, in turn, was a linchpin of the Green Revolution, and ultimately the emergence of today’s global integrated economy.

That control and manipulation of water should be a pivotal axis of power and human achievement throughout history is hardly surprising. Water has always been man’s most indispensable natural resource, and one endowed with special, seemingly magical powers of physical transformation derived from its unique molecular properties and extraordinary roles in Earth’s geological and biological processes. Through the centuries, societies have struggled politically, militarily, and economically to control the world’s water wealth: to erect cities around it, to transport goods upon it, to harness its latent energy in various forms, to utilize it as a vital input of agriculture and industry, and to extract political advantage from it. Today, there is hardly an accessible freshwater resource on the planet that is not being engineered, often monumentally, by man.

Whatever the era, preeminent societies have invariably exploited their water resources in ways that were more productive, and unleashed larger supplies, than slower-adapting ones. Although often overlooked, the advent of cheap, abundant freshwater was one of the great growth drivers of the industrial era: its usage grew more than twice as fast as world population, and its ninefold increase in the twentieth century rivaled the more celebrated thirteenfold growth in energy. By contrast, failure to maintain waterworks infrastructures or to overcome water obstacles and tap the hidden opportunities water always presents has been a telltale indicator of societal decline and stagnation.

Every era has been shaped by its response to the great water challenge of its time. And so it is unfolding—on an epic scale—today. An impending global crisis of freshwater scarcity is fast emerging as a defining fulcrum of world politics and human civilization. For the first time in history, modern society’s unquenchable thirst, industrial technological capabilities, and sheer population growth from 6 to 9 billion is significantly outstripping the sustainable supply of fresh, clean water available from nature using current practices and technologies. Previously, man’s impact on ecosystems had been localized and modest. Across heavily populated parts of the planet today, much of the rivers, lakes, and groundwater on which growing societies depend are becoming dangerously depleted by overuse and pollution. As a result, an explosive new political fault line is erupting across the global landscape of the twenty-first century between water Haves and water Have-Nots: internationally among regions and states, but just as significantly within nations among domestic interest groups that have long competed over available water resources. Simply, water is surpassing oil itself as the world’s scarcest critical resource. Just as oil conflicts were central to twentieth-century history, the struggle over freshwater is set to shape a new turning point in the world order and the destiny of civilization.

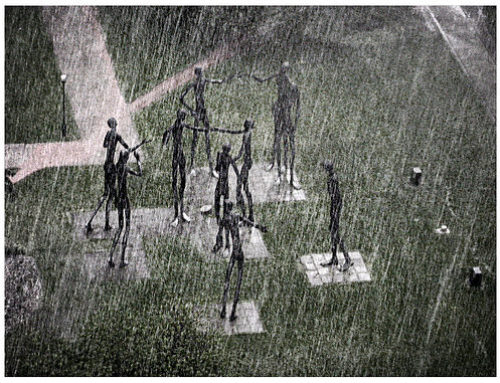

Humanitarian crises, epidemic disease, destabilizing violence, and corrupt, failed states are already rife in the most water-deprived regions, where 20 percent of humanity lacks access to sufficient clean freshwater for drinking and cooking and 40 percent to adequate sanitation. Those who have predicted that the wars of the twenty-first century will be fought over water have foremost in mind the water-starved, combustible Middle East, where water looms omnipresently over every conflict and peace negotiation, and where those with oil are desperately trying to postpone their day of reckoning by burning it to pump dry aquifers and desalinate seawater in order to sustain farms and modern cities in the desert. Freshwater is an Achilles’ heel of fast-growing giants China

and India, which both face imminent tipping points from unsustainable water practices that will determine whether they lose their ability to feed themselves and cause their industrial expansions to prematurely sputter. The buffeting global impact will be especially far-reaching for the fates of water-distressed developing nations that are reliant on food imports to feed their swelling, restive populations. While the West, too, has some serious regional water shortages, its relatively modest population pressures and generally moist, temperate environments make it an overall water power possessing significant water resource advantages. If aggressively exploited, these advantages can help relaunch its economic dynamism and world leadership.

The lesson of history is that in the tumultuous adjustment that surely lies ahead, those societies that find the most innovative responses to the crisis are most likely to come out as winners, while the others will fall behind. Civilization will be shaped as well by water’s inextricable, deep interdependencies with energy, food, and climate change. More broadly, the freshwater crisis is an early proxy of the twenty-first century’s ultimate challenge of learning how to manage our crowded planet’s resources in both an economically viable and an environmentally sustainable manner. By grasping the lessons of water’s pivotal role on our destiny, we will be better prepared to cope with the crisis about to engulf us all.

Reprinted from Water: The Epic Struggle For Wealth, Power, And Civilization with permission from HarperCollins Publishers. Copyright 2010 by Steven Solomon