Temescal Creek

The Temescal Creek waterhood, spanning from the rolling North Oakland hills to the mudflats of Emeryville Crescent, has supported diverse forms of life over the millennia. Giant camels, huge ground sloths, mammoths and giant beavers roamed the shorelines after the last Ice age filled in the vast meadowland of what is now the Bay and the dry land that extended nearly to the Farlonne Islands.

Take the Walking Waterhoods Temescal Creek Tour

Welcome to your great opportunity to learn the human and natural history of Temescal Creek Watershed. The tour is broken into 1-2 mile sections for easy walkability. You can walk this tour virtually on the PocketSights website or in the tour location using the Pocketsights app. A sound will alter you once you’ve reached the point of interest.

Not only can you take the tour, but as importantly, you can contribute to the tour. Do you have a story to tell about a point in the watershed? Did you see something on the walk that you think others will appreciate? Great, send an email to info@whollyh2o.org

To walk it using your phone, download the Pocketsights app and it will show you all the local tours, ours included. Look for “Walking Waterhoods”. Use these QR codes for

Enjoy these Virtual Tours of Temescal Creek

History

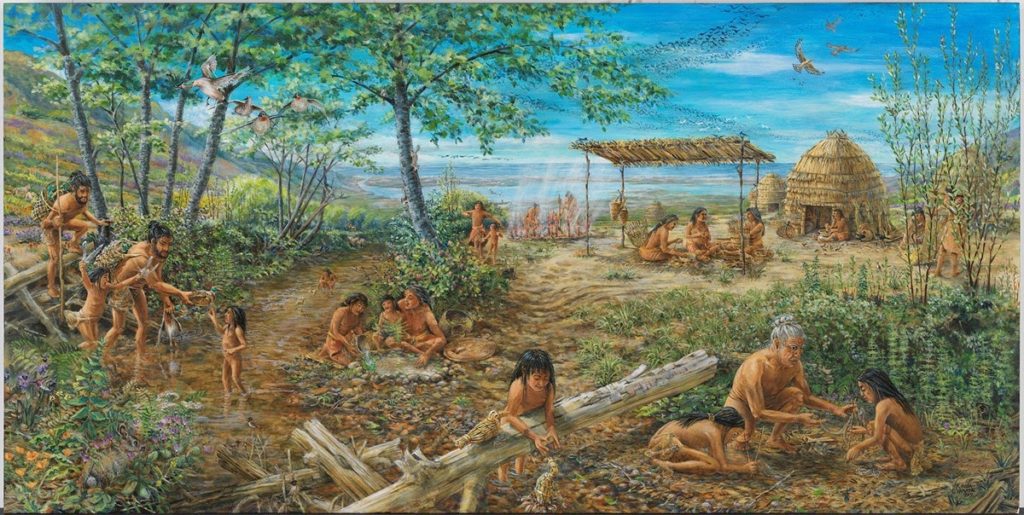

Small tribelets of Ohlone thrived in the native annual grasslands along with abundant grizzlies, tule elks, and millions of shorebirds, moving up and down the creek with the seasons from 2,500+ years ago until Spanish colonization beginning mid-1700s. More recently with much of the creek buried by a concrete jungle, humans have lost a real sense of Temescal Creek watershed of today. While much of it is now underground, on any given day you might see rainbow trout, river otters, and dragonflies meandering about in segments that remain open. In other parts of town, you can celebrate the rich history that lies beneath the streets through reconstructed creek sections, art pieces and memorials found along its path. Most importantly, you can reconnect with the flora and fauna that have been living around you all along. They are your neighbors, your watershed neighbors, all sharing the Temescal Creek Waterhood.

The Huichan Ohlone were the first people to settle the banks of Temescal Creek. They lived in tule reed houses built alongside the creek and on top of shellmounds. A willow thicket at the mouth of the creek and adjacent mudflats provided a rich ecosystem suitable for hunting, fishing, and gathering. Tule reeds provided material for boats, houses and sweathouses. The Huichan gathered oysters, shrimp and clams from the marshes, hunted elk, deer and small mammals among native annual grasses, fished for steelhead and salmon in the creek, feasted on beached whales and harvested acorns in the hills.

The Huichan Ohlone lived in small independent tribelets along Temescal Creek until the late mid-1700’s when Spanish explorers and missionaries arrived in the SF Bay Area. Missionaries and soldiers brought the Ohlone into the missions and forts they established around the Bay while European diseases, and European/native skirmishes decimated native populations. Within 100 years, nearly all of the 17,000 Ohlone and Miwok peoples that had lived in the Bay Area were gone and the land carved into rancherias divided between original Spanish/Mexican settlers to the area.

Ohlone in a Tule Boat on San Francisco Bay, 1816 by Louis Choris

In 1820, the Spanish government was granted to the Peralta family granted 44,000 acres of land, including the 6.7 square-mile stretch of the Temescal Creek watershed. The Peralta’s wealth and influence formed Rancho San Antonio into the social and commercial center of the area. The cattle they brought in replaced the tule elk, prong horned deer and destroyed the native grasslands, compacting the soil and forever altering the shoreline ecology. Soon after, gold was discovered, and the subsequent arrival of tens of thousands of European and African American prospectors led to the rapid destruction of habitat, radical reduction in species numbers and varieties – the now extinct California grizzlies were killed by the thousands for sport, along with overhunting of elk, deer, whales, beaver, trout, salmon and many other species that were once found as a matter of course throughout the watershed.

by Amy Hosa & Linda Yamane, 2019.

The proliferation of non-Natives caused rapid urbanization.As a result, the creek was altered in a variety of ways. In 1868, the creek was dammed directly over the Hayward Fault to create Lake Temescal, a source of drinking water for the burgeoning city of Oakland. The fast rising population made this water supply obsolete within a few years and Lake Chabot came on line, both being built with Chinese labor by Anthony Chabot using hydraulic mining equipment and wild horses. Wealthy white artists, writers camped by the edges of the Lake. As neighborhoods grew around Temescal Creek (and other waterbodies), so did paved roads, highways, cement sidewalks and stormwater, With the creek no longer a vital source of water, it became trapped from naturally moving its course from side to side due to development along the creek. became less connected to their watershed. Buildings were increasingly built in proximity to the creek. By the mid 20th century, Temescal Creek was considered by many to be “a nuisance” filled with trash and sewage which overcame its banks with flood waters, This led most of the creek, below Lake Temescal being funneled into culverts and buried.

Today, Temescal Creek still begins and ends its journey in the daylight, while most of the creek is hidden underground. Over the past 200 years, many advocates have brought awareness around the value that a healthy creek system can bring to the community. Visit the Rockridge-Temescal Greenbelt and see the underground path it takes. Or visit Garber Park to see ongoing restoration efforts of the creek’s banks.

What You Will See

As you make your way along Temescal Creek, you’ll discover that it supports a diverse range of plants and animals in the few places where the creek is above ground. A very different host of species live where the creek is buried, no longer hinting at a substantial aquatic presence.

North American River Otter, photo by hydrospheric CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

Toward the upper reaches of the creek in its headwaters, trees such as redwoods, bigleaf maple, live oaks, and buckeyes grow alongside its banks. These trees stabilize its banks against erosion and provide food for insects and shelter for animals. Black-tailed deer are a common sight in the area, but if you’re lucky, you’ll get to see some other mammals like river otters munching on fish or brush rabbits bounding into blackberry thickets.

At the mouth of the creek in the Emeryville mudflats, there are some last vestiges of marshlands with aquatic vegetation like pickleweed and cordgrass. They provide the perfect nesting ground for birds such as egrets and herons as well as cover for small foraging mammals like the salt marsh harvest mouse.

The brackish, still waters allow populations of small fish, mammals, birds, reptiles, and amphibians to thrive, which are, in turn, often hunted by kites, hawks, harriers, and other birds of prey. This shoreline habitat is also particularly important to migratory bird species that travel along the Pacific Flyway. A variety of shorebirds and ducks visit the Emeryville Crescent in fall and winter making it a crucial stop halfway through their journey.

Pickleweed photo by Bas Kers CC BY-NC-SA

The Pacific Flyway, with the San Francisco Bay circled in black

Want to help naturalists document species in the Temescal Creek watershed? Download the iNaturalist app and start contributing your own photos of the flora and fauna you discover.

What’s Being Done

The Temescal Creek watershed has experienced high amounts of urban development which, in turn, led to the exposed creek flooding and therefore being culverted and buried. But this has not solved the problem of excess stormwater and pollution, as hard, impermeable surfaces continue to this day to increase in coverage, which in turn requires increased flood and pollution control measures. Proven methods of flood control include replacing parking lots and sidewalks with open soil or permeable materials that allow water to percolate (drain) into the soil, collecting rainwater onsite before it becomes troublesome stormwater full of pollutants and chemicals shooting down into storm drains leading the culverted creek and creating green roofs that absorb and filter water with vegetation. To combat pollution, several organizations educate the community on how to conserve water and keep pollutants out of the watershed.

Here are a few of the local environmental groups that have stepped in and made an effort to help restore and maintain this watershed:

Green landscaping at Temescal Creek Park

Friends of Rockridge Temescal Greenbelt are the creators of the beloved FROG Park in North Oakland. Supported by a coalition of local leaders and organizations including Friends of the Rockridge-Temescal Greenbelt, Oakland Parks and Recreation Foundation, Temescal Neighbors Together, Friends of Temescal Creek, DMV Neighbors Association (DNA), Rockridge and Temescal merchant groups with the City of Oakland’s Office of Public Works and Office of Parks & Recreation.

Garber Park Stewards regularly hold restoration and erosion prevention projects along Claremont Creek, the northern fork of the Temescal Creek watershed, and participate in the annual Creek to Bay cleanup. These projects are funded by the Claremont Canyon Conservancy, which recently created the Willow Trail, a fire trail that runs parallel to Claremont Creek further up the canyon. This organization is also responsible for planting fire-resistant species such as California Redwood and removing fire-prone trees such as eucalyptus and pine. These mitigation efforts prevent fires from endangering our creek systems.

Friends of Five Creeks, an all-volunteer creek and watershed restoration group, consults with civil engineers on a variety of green projects that reduce flooding in the Temescal Creek watershed. You can view some of the work they’ve done on their site, Blue-Green Building.

Friends of Temescal Creek is one of the original “Friends of” a creek organizations in the Bay Area. This group is currently on hiatus and lacks a contact.

Get Involved

Protecting and restoring our watersheds is not only good for the species that rely on these water sources, but it’s also good for us too. Here are a few ways you can get involved to help us ensure the health of the Temescal Creek watershed.

Adopt Temescal Creek through Alameda County Public Works

Join the folks of FROG and help care for the park grounds

Keeping storm drain inlets clear helps maintain water quality and prevent flooding during storms.

Fun Facts!

Lake Temescal was a popular camping spot in the 1800’s among bohemian artists and writers.

There’s a faux creek in Frog Park that mimics the real one below.

Temescal Creek’s name comes from the Aztec word Temescalli meaning sweat house.

Additional Resources

For more information on the history, restoration, and recreation of the Sausal Creek watershed, be sure to visit the links below.

The Friends of Sausal Creek have compiled some great lists of what you can see:

A Creek Ran Through It

Hover for more info!Links

A history of the Temescal neighborhood by Oakland North, a project of the UC Berkeley Journalism School.

Many A Creek Runs Through It

Hover for more info!What Flows Beneath Temescal

Hover for more info!Potemkin Creek: I Can’t Believe It’s Not Nature

Hover for more info!Links

Potemkin Creek: I Can’t Believe It’s Not Nature

Thesis exploring the processes that created the faux creek in Frog Park.

Geomorphic Responses to Urbanization Along Temescal Creek

Hover for more info!Links

Geomorphic Responses to Urbanization Along Temescal Creek

Paper on the physical and hydrological aspects of Temescal Creek.

Emeryville’s History

Hover for more info!Temescal Creek Watershed Organizations

Wholly H2O and the Walking Waterhoods program couldn’t exist without our trusted partners. We offer a big thanks to those who have worked with us and have helped educate, maintain, and restore our San Francisco Bay watersheds.