-

The opportunities for keeping sewage out of the oceans are everywhere (where there are humans). The Zandaam cruise ship, that takes passengers on a breath-taking tour of Alaska, is pushing into new (waste) waters!

A below-decks tour of the recycling operations of a high-end cruise ship

posted by InvestigateWest at Wednesday, June 16, 2010

By Katie Farden

InvestigateWest

While the 1,432 passengers aboard Holland America’s Zaandam, are enjoying a five-course meal at one of the ship’s plush dining venues or unwinding with a hot-stone massage in the vessels’ full-service spa, crew are bustling below, sorting out tons of waste and recyclables.

The Zaandam is one of 11 ships operated by six major cruise lines making weekly departures for Alaska from Seattle’s Elliot Bay this summer.

Environmental organizations have long charged cruise lines with producing extreme quantities of waste. According to Bluewater Network, which merged with San-Francisco-based Friends of the Earth (FOE) in 2005, even a week-long trip generates serious garbage:

“A typical cruise ship on a one-week voyage generates more than 50 tons of garbage, two million gallons of graywater (waste water from sinks, showers, galleys and laundry facilities), 210,000 gallons of sewage, and 35,000 gallons of oil-contaminated water.”

But cruise industry representatives maintain crew aboard their vessels are making cutting-edge efforts to be more sustainable.

Everything Zaandam passengers throw away, said Joe Parks, one of Holland America’s environmental officers, is sorted by crew members and stored on the ship until the vessel can offload it at a port.

The sorting room (pictured above) is two floors below the first passenger deck. The room has a full-time staff of 6-8 members who separate glass, paper and cardboard, aluminum cans and trash. The recyclable materials are compressed: boxes are broken down and machines hum and clamor, pressing bucketloads of glass and cans.

The crew stores the waste and recycled materials until the ship docks in Vancouver, Canada, where a recycler picks up the load.

Excess cooking oil is also collected in the sorting room. The crew burns the oil to help power the engines, saving the vessel about $480 a week in fuel costs.

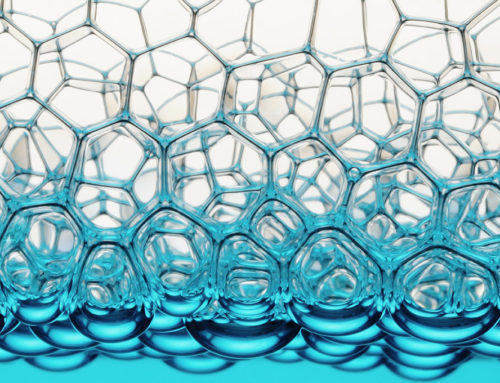

The Zaandam’s sewage treatment system is called the Zenon. Through the Zenon, graywater is pumped into a tank and then filtered through a bioreactor, in which bacteria reduce harmful toxins like chlorine, fecal mater and ammonia.

By the end of the process, Parks said, the water quality is close to that of drinking water.

“It’s drinkable, but I don’t feel like having a taste,” said engineer Michael Hall, who works in advanced wastewater processing aboard the Zaandam.

Holland America has fifteen cruise ships in its fleet. Twelve vessels are equipped with advanced wastewater treatment systems, like the Zaandam.

According to Marcie Keever, FOE’s Clean Vessels Campaign director, the Zaandam is one of the industry’s more environmentally conscious vessels.

“[The Zaandam] is doing a better job in complying with Alaska’s strict water laws,” she said.

In Alaska, law forbids cruise ships from discharging certain contaminants into state waters. A 2006 voter initiative requires the Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation regulate not only fecal matter, but also discharges of ammonia, copper, nickel and zinc.

The Zaandam did not receive any notices of violation in Alaska waters in 2009 or 2008.

Also below the Zaandam’s deck, five 12-cylinder diesel engines power five 18-foot generators. The crew has to power up every engine to reach its maximum speed of 23 knots.

Though the Zaandam is not equipped to use shore power–a system in which ships dock, turn off their engines and plug in to generators at a city’s port to reduce engine emissions–the vessel is outfited with the cruise industry’s first 1.5 million dollar saltwater scrubber.

According to Holland America, scrubing technology has long been used to reduce sulfer dioxide emissions at oil and coal power plants. The scrubber on the Zaandam–which the EPA provided $300,000 to help fund–combines the calcium carbonate in saltwater in a chemical reaction with engine gasses to reduce the ship’s emissions.

The saltwater scrubber, installed on the Zaandam in 2007, is still in a pilot phase. According to Holland America, the technology is expected to reduce the vessel’s sulfer dioxide emissions by 95 percent.

Keever points out, however, that the scrubber, which uses 360 tons of seawater per hour, may create another pollutant the ship would have to deal with.

“I don’t know how successful or not that technology has been on the air quality side,” she said. “But it does produce sludge that’s highly acidic. It could be a problem having to dispose of that.”

Various air and water treatments produce sludge, which is a semi-solid residue. This waste can sometimes be hazardous, according to the EPA.

“People don’t realize how many waste streams there are aboard cruise ships,” Keever said.

Oily bilge water is pollutant produced directly from the ship’s engines. A mixture of water and leaked oil from auxiliary engines boilers and evaporators, oily bilge water threatens marine life and coastal habitats when it enters the ocean, according to environmental group Oceana.

According to a 2008 EPA report, oily bilge water is the most widespread form of cruise ship pollution.

One Parks’ responsibilities as the ship’s environmental officer is keeping the concentration of oil in the bilge water the Zaandam leaks into the ocean to a minimum. Federal law requires cruise vessels release only liquids with an oil concentration of 15ppm or lower.

“We’re usually way below that,” said Parks of the concentration of water the Zaandam pumps into the sea.

He adds that the cruise industry as a whole has made strides to be more environmentally conscious in recent decades.

“You don’t hear about cruise lines doing things they used to do 20 or 30 years ago, like crew dumping big cans of trash overboard, he said. “We all have standards now.”