-

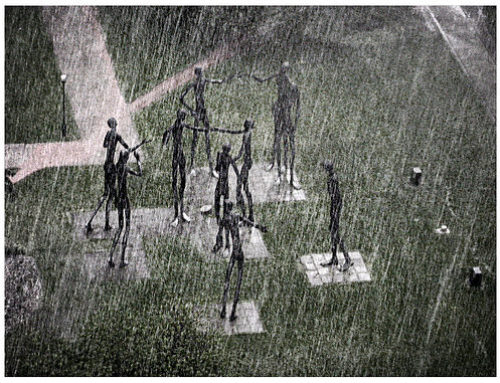

Many water delivery systems in California are aged and falling further and further into dismal condition. This can lead to wasted water and underground sewage leakages. Here’s a northern California system that draws on Hetch Hetchy supplies that is undergoing repairs.

New Irvington Tunnel One of Many Water System Improvements

Written by Gail Schickele

The New Irvington Tunnel project in Alameda County will break ground in September as part of the $4.6 billion Water System Improvement Program (WSIP) launched in 2002 to repair, replace, and seismically upgrade the aging San Francisco Regional Water System, often referred to as the Hetch Hetchy system. Owned and operated by the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission (SFPUC), the system delivers drinking water to 2.5 million people in the five counties of San Francisco, San Mateo, Santa Clara, Contra Costa, and Alameda.

“Our regional water system is considered by many to be an engineering marvel — it is a gravity-fed system that spans 167 miles from the Hetch Hetchy Reservoir in Yosemite National Park to San Francisco,” explained WSIP Director Julie Labonte in a recent interview with Brown and Caldwell Water News. “WSIP is a huge capital improvement program that consists of 86 projects that enhance our ability to provide reliable, affordable, high-quality water to all our customers in the Bay Area.”

Built between 1928 and 1930, the existing Irvington Tunnel is an important part of that water delivery system because it connects the water supplies from the Sierra Nevada Mountains and the Alameda Watershed to Bay Area water distribution systems serving SFPUC customers. Expected to be completed by early 2014, the new 3.5-mile tunnel will lie parallel to the existing tunnel between the Sunol Valley south of Highway I-680 in unincorporated Alameda County and the Mission San Jose district in Fremont. The Town of Sunol receives the majority of its water from the SFPUC and the City of Fremont receives approximately 30 percent of its drinking water from the system.

Conventional mining methods — primarily road header tunneling and limited, controlled detonation — are planned for the tunnel’s internal diameter of 8.5 to 10.5 feet. Disposal of excavated materials from the Irvington Portal in Fremont will go to a spoils site in the Sunol Valley. Spoils disposal is planned to create a visual barrier to new quarry operation just north of the San Antonio Pump Station near the intersection of Calaveras Road and I-680. Potentially contaminated spoils will be screened, separated, and if found to contain contaminants, hauled to a permitted landfill.

The existing bridge across Alameda Creek will be permanently replaced, initially to accommodate temporary construction traffic as well as ongoing SFPUC Alameda West Portal operations.

A groundwater management plan has been developed that includes two years of monitoring wells, springs, creeks, wetlands, and environmental habitat to minimize the impact to the local groundwater.

According to the Environmental Impact Report, the project could contribute to unavoidable impacts on stream flow in Alameda Creek between the diversion dam and the confluence with Calaveras Creek, while other impacts — aesthetics; air quality; biological resources; cultural resources; geology, soils and seismicity; hazards and hazardous materials; hydrology and water quality; land use; noise and vibration; recreation; transportation and circulation; mineral and energy resources; agricultural resources; and utilities and service systems — are expected to be mitigated to a ‘less than significant’ level.

The Bigger Picture: WSIP and Seismic Issues

The U.S. Geological Survey predicts a 63 percent chance of a major earthquake in the Bay Area within the next 30 years. Earthquake damage to the Irvington Tunnel would severely disrupt the supply of emergency water for health and fire protection for an extended period of time. As a whole, the San Francisco Regional Water System remains at risk.

“Although the Hetch Hetchy water system is truly an engineering marvel, some critical elements are seismically vulnerable,” Labonte said. “It’s not a matter of if, but when a major earthquake strikes — we are truly in a race against time.” With the system crossing three of the nation’s most active earthquake faults, this is first and foremost a seismic reliability program, she said.

Crucial portions of the regional water system, which was built in the early to mid-1900s, cross over or near the Hayward, San Andreas, and Calaveras faults. Because it’s been estimated that a major earthquake on any of these faults would likely cut off most customers from their water service for at least 30 days, one of the primary goals of the WSIP is to deliver water to 70 percent of customers within 24 hours of a major earthquake.

Since the Loma Prieta earthquake, Bay Area counties have worked to develop “intertie” systems so they might share water supplies in an emergency. SFPUC has completed such programs with both Santa Clara and East Bay water districts.

The Hetch Hetchy water supply is supplemented with surface water from rainfall and runoff captured in two local watersheds: the 23,000-acre Peninsula Watershed in San Mateo County with reservoirs in Crystal Springs, San Andreas, and Pilarcitos, and the 35,000-acre Alameda Watershed in Alameda and Santa Clara counties, collected in the Calaveras and San Antonio reservoirs.

WSIP projects span seven counties from San Francisco (“Local Projects”) to areas across the Central Valley, southern Alameda and Santa Clara counties, and up the peninsula (“Regional Projects”). Regional projects are organized into five regions: San Joaquin, Sunol Valley, Bay Division, Peninsula, and San Francisco. Projects vary in size and complexity involving both the development of new facilities and improvements to existing facilities, such as dams, reservoirs, pipelines, tunnels, treatment facilities, pump stations, and water storage tanks.

Nearly 56 of 86 projects are either in construction or completed, and some of the program’s largest and most complex projects are entering the construction phase. At present, more than $1.5 billion worth of projects are in construction and WSIP has final approval for all funds required to complete the program in late 2015. WSIP projects are projected to create nearly 28,000 jobs and nearly 11,000,000 craft hours.

“We’re building three new tunnels — including the first under San Francisco Bay — a new dam and the largest UV treatment facility in California,” Labonte explained. “We’re also retrofitting our two existing treatment plants and installing miles of pipelines throughout the system. Our biggest technical challenge is coming up with a pipeline design at the Hayward Fault crossing that can withstand a 7-foot displacement.”

Overall, capital improvements are expected to enhance SFPUC’s water delivery to 1.7 million people in Alameda, Santa Clara, and San Mateo counties, and to 800,000 retail customers in San Francisco. The proposed WSIP is structured to cost-effectively meet water quality requirements, improve seismic and delivery reliability goals through the year 2030, and meet water supply objectives until the year 2018.

“We’ll revisit the water supply project and how we operate the system in 2018,” said SFPUC spokesperson Betsy Rhodes.

Wholesale and retail customers who benefit from the Hetch Hetchy water system will pay for the capital improvement program in proportion to the amount of water delivered. One-third will be paid by San Francisco retail customers and two-thirds through the 26 cities, water districts, and utilities that buy water from SFPUC for resale to their local service areas. SFPUC estimates that Bay Area water rates to residents and wholesale customers will remain at the middle to low end of California’s water rate spectrum.

For more information, visit www.sfwater.org or contact Betsy Rhodes at (415) 554-3240.