Recently, I put a query out on a citizen science email list. “Who is doing watershed-related citizen science?” While I am indeed writing a separate blog on this topic, it was a trick question of sorts because the truth is that wherever you are, you’re in a watershed of some scale and whatever you’re doing, you are impacting that watershed (and likely several other) at any given moment. But we’ve all become so disconnected from land, water and ecosystems, that we’ve lost touch with that awareness. And even naturalists and biologists don’t necessarily hold the watershed framing in the forefront of their minds as a context for their work.

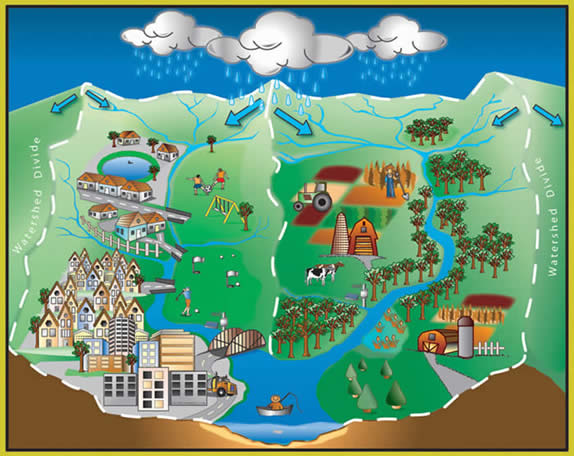

Watersheds are generally presented through the lens of water and geography – aka, how water is moving through the landscape.

Image: Boone County Stormwater Management

It’s a land area that channels rainfall and snowmelt to creeks, streams, and rivers, and eventually to outflow points such as reservoirs, bays, and the ocean. (NOAA)

A watershed describes an area of land that contains a common set of streams and rivers that all drain into a single larger body of water, such as a larger river, a lake or an ocean. (Penn State Brandywine)

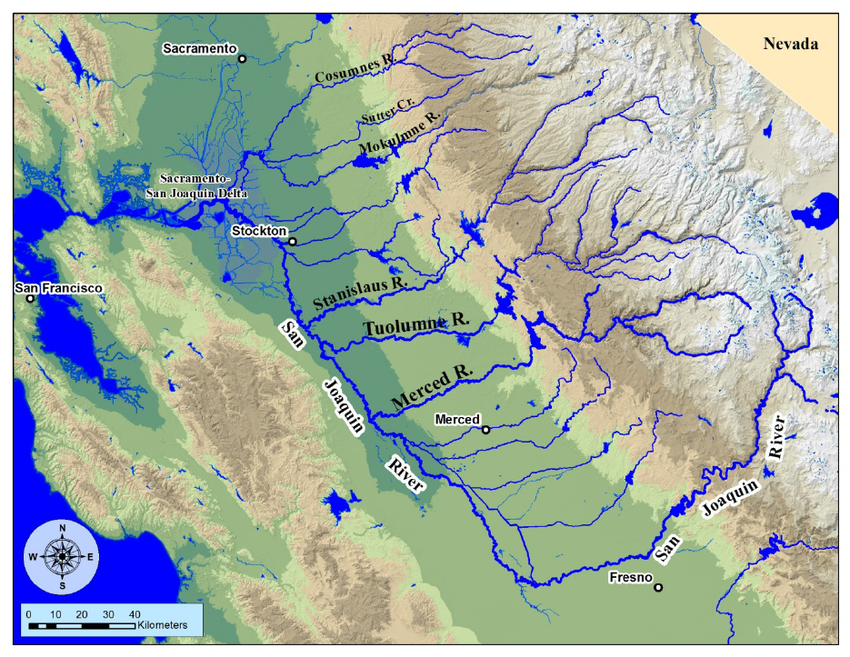

In this above image, there are two full watersheds shown, each with its own river. At the bottom the rivers merge and form one river which demonstrates how smaller watersheds can be contained within a larger watershed. Another great visual example blow is the San Joaquin River Watershed which contains numerous very large watersheds (Consumnes, Sutter, Mokelumne, Stamislaus, Tuolumne, Merced Rivers’ watersheds). Numerous of these watersheds are becoming increasingly denigrated by having +/- 80% or more of the water removed from the river channel for human use. The description below the image exemplifies why this is – considering watersheds as water only, treating watersheds as resources rather than living systems, and therefore foregrounding the needs of humans, our infrastructure, our transportations systems, building dams for reservoirs for our drinking our drinking, agricultural and industrial uses.

Image by William Stringfellow

(T)he watershed provides a primary source of drinking water for 25 million Californians, irrigation for 7000 square miles of agriculture, and includes important economic resources such as California’s water supply infrastructure, ports, deepwater shipping channels, major highway and railroad corridors, and energy lines. In the Delta specifically, declining water quality and increasing demand for limited water resources are the subject of intense review and planning to protect this valuable resource for the future… Water flows in the San Joaquin River have been substantially modified by dams and diversions that remove 95% of the water from the river at Friant Dam. These diversions cause the San Joaquin River to be dry for more than sixty miles of its course. (amended from EPA.gov)

NOTE: THIS IS NOT NORMAL.

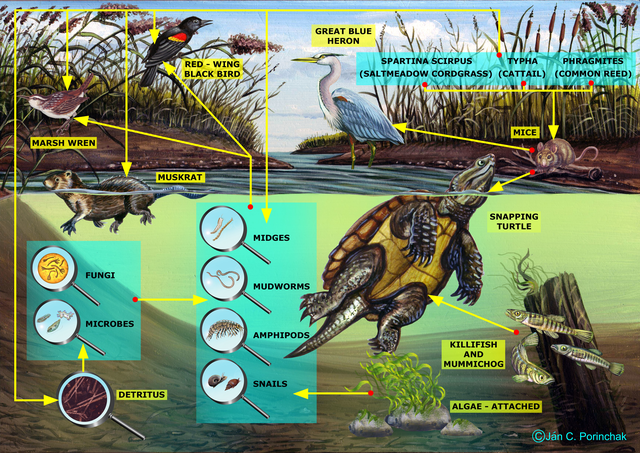

But, honestly, a watershed is much more than water’s voyage through space over time. It’s a lens through which to understand the web of interactions of living and nonliving elements that we call an ecosystem. Basically, it’s a neighborhood of living and nonliving elements (like all neighborhoods) that directly and indirectly impact one another – what I call a waterhood. Thinking of surrounding flora and fauna as neighbors (some I get along with – racoons, opossums, spiders, skunks native bees, wasps, flies and butterflies) and some that are more challenging (termites, argentine ants, rats, cockroaches) gets me thinking about how my actions affect them and vice versa. As international rivers describes, “A watershed also includes all the humans, plants and animals who live in it, and all the things we have added to it such as buildings and roads. Everything we do affects our watershed – from washing clothes and growing food to mining, commercial farming, and building roads or dams. The reverse is also true: our watershed affects everything we do, by determining what kinds of plants we can grow, the number and kinds of animals that live there, and how many people and livestock can be sustainably supported by the land.”

Now let’s look at a definition of neighborhoods that will leave you really pondering how this applies to your relationships with your nonhuman waterhood neighbors.

“Neighbourhood is generally defined spatially as a specific geographic area and functionally as a set of social networks. Neighbourhoods, then, are the spatial units in which face-to-face social interactions occur—the personal settings and situations where residents seek to realise common values, socialise youth, and maintain effective social control.” (Schuck, Amie and Dennis Rosenbuam 2006 “Promoting Safe and Healthy Neighborhoods: What Research Tells Us about Intervention.” The Aspen Institute.)

Image from Animals and Society Institute

What would it look like to consider eucalyptis trees, sujaro cactus, racoons, coyotes, bear, ticks, redwoods, scotch broom as neighbors? How well do you know them (or whatever species is local to you)? If all your neighbors were from other countries and you didn’t know their language but needed/wanted to interact with them, what would you do? Well, dang, I bet you’d either get some good sign language going, get a translator, or you’d pick up a few words of Hindi, French, Hosa, Spanish, Arabic. But, what I personally experience is that most languages of my neighbors that humans probably knew at one time perhaps centuries ago have long since been forgotten, and I am having to make a concerted effort to get to know them now.

Those of us in urban settings are at a disadvantage, as those in more rural settings are still often in an overt interactive relationship and therefore knowledgeable of their physical watershed as well as their waterhoods. Like the friend who heard a ruckus in his kitchen early one morning and woke to find a bear cub rifling through his fridge.

Photo by Brian Tierney

Humans pave pathways (highways, roads, sidewalks) for ourselves and imagine that only we belong on them or need to use them. We build living and work structures, gardens, and infrastructure then imagining that humans are the only ones that will inhabit and use them.

Image by Jaymi Heimbuch

We’re surprised and run to Home Depot to find products to expel our waterhood neighbors from building, yards and parks, even if it takes poisoning them, our pets, the food we’re growing and ourselves. It doesn’t matter to us what waterhood neighbors were already living there, the boundaries of their territory, their migration patterns or daily mobilization or food and water needs, and the benefits they bring by creating an ecosystem with us.

What is clear is that many developed and urbanized populations, particularly in the US and Europe, have come to think of the ecosystem (aka nature) as something outside of ourselves, a place from which to draw natural resources, as part of ecosystem “services” to homo sapiens. Industrialized, capitalized humans consider themselves largely apart from their ecosystems rather than a part of their ecosystems. We focus on individual “resources” as if we are living in a post-ecosystem-dependent world, and each part is not connected to the rest. We have forgotten that we ARE ecosystem in the same way that we ARE water. We ARE nature. We ARE mammals. We ARE animals. We do have natural instincts and much of our behavior, whether we admit it or not, coms from these natural instincts.

We forget the hip bone is connected knee bone and the knee bone – that bears poop in the woods and when they do, they poop fish emulsion that fertilizes trees and plants that hold that soil in place, so the trees can prefilter the water that makes its way into air and the groundwater or into the river we and many other species use for drinking. And because we are using that water (maybe as much as 3.5 gallons at a pop to flush .03 gallon of pee to a waste treatment plant), our other neighbors in our water supply waterhood do not have access to that water. We insulate ourselves from earth processes and then imagine that we can actually control them – all of them. Rather than becoming an active and informed part of various life cycles, including the water cycle, we stand apart and ask how we can give us all we need and desire, bending them to our will or thriving or eradication. And that causes us to remain ignorant of interconnected natural processes, which leads to poor decision making in the short and long run.

A waterhood is a web in which we ourselves have a crucial role, as demonstrated by our starring role in instigating the current Sixth great extinction). Scientists estimate we’re now losing species at 1,000 to 10,000 times the background rate, with literally dozens going extinct every day, suggests the Center for Biological Diversity. This is a mighty role for just one of the roughly 8.7 million species, by one 2011 estimate. How proficient we have become at erasing other species.

So, when I see this sticker over my kitchen or bathroom tap, I don’t just think about water moving through geography into a piped water delivery system to a water treatment plant to my tap, I think about all the whole waterhood, and am as thrifty with my water as possible. (Whether the water agency leaves more water instream as a result of conservation is another discussion.) Why? Because there are hundreds of thousands of neighbors also using that water, and I want to have their back, in the same way they have mine by maintaining the watershed for the water I am literally made of every day.

This is exactly why Wholly H2O, which has historically focused on water conservation and water reuse, has been doing nature nerd surveys (aka community/citizen science bioblitzes) in waterhoods for the last two years. We’re getting folks out to get to know their watershed ecosystem neighbors so that they have a deeper sense about what it means to be watershed-wise. It’s my firm belief that becoming watershed-wise inspires people to conserve and reuse water in a more profound way than any flashing sign that reads “Save Water.” We truly are ALL in this together.

Check out our Waterhood page and join us at upcoming Nature Nerd Bioblitz in the SF Bay Area and beyond.